After coming home from a long day on the job, most people would dread getting a call from the office saying they needed to get back to work immediately, and then for another 6 hours or more. This couldn’t be farther from the truth for us, the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Arctic Beringia wolverine research crew. On March 30th, that call was a satellite-transmitted message telling us that one of our wolverine live traps had closed. What was inside was unknown; what we did know is that we were excited to find out, that night was quickly encroaching, and that the temperatures were already below zero Fahrenheit.

The moment a pin is pulled from the satellite communicator as the trap closes, prompting us to drop what we are doing and head to the trap. Photo credit: Matt Kynoch.

Despite the timing and dropping temperatures, it was a moment we had been eagerly anticipating for weeks. We’d seen tracks and pictures from remote cameras of an elusive wolverine making somewhat liberal use of the area, but this animal had consistently avoided our traps. After a full day’s work covering around 80 miles on rough and non-existent trails, following wolverine tracks and hauling gear, we ate a quick dinner and excitedly regrouped. Based on tracks we’d seen in the area, the anticipation of finding a wolverine in our trap was high – but we were cognizant to the fact it could be a fox.

Our snow machines made it the 8 miles to the trap in less than an hour, though the journey to a triggered trap can feel like an eternity when you’re bubbling with the anticipation of coming face to face with a new wolverine in a 30”x 5’ wooden box. A quick peek inside the trap revealed a small, surprisingly docile wolverine, more concerned with slobbering over the sweet-smelling carcass we had used as bait, than reacting to our flashlights and prying eyes. Others we’d caught earlier in the season would make their displeasure at capture much better known as they paced and growled in the dust and splinters of attempts to chew their way out of the boxes.

The wolverine trap (left) and Arctic Oven tent where the wolverine is processed in relative warmth to the sub zero temperatures outside. The northern lights in full spate. Photo: Matt Kynoch.

On this night, we had captured a young male, on the small side for male morphology. After a carefully placed anesthetic injection in the rump from a jab stick, essentially a syringe on the end of a pole, the animal could be moved inside our bright yellow Arctic Oven tent. These tents are an arctic camper’s dream, big enough to stand in, and also able to accommodate a fire due to vents in the roof – in our case we heated it with a roaring propane heater. We laid the sedated wolverine on blankets and hot water bottles before measuring him, attaching a satellite collar and an ear tag, and applying antibiotic ointment to a small wound above his left rear leg that looked to have been sustained a couple of days earlier. None of our other captures this year had any sort of injury. There was no indication as what may have been the cause, but it was nevertheless a reminder of the dangers of being a predator in this unforgiving environment. Within an hour our work was done and the small male was placed back in the trap in a blanket, to recover from the immobilization drugs.

Wolverine and researcher come face to face for the first time. Photo credit: Matt Kynoch.

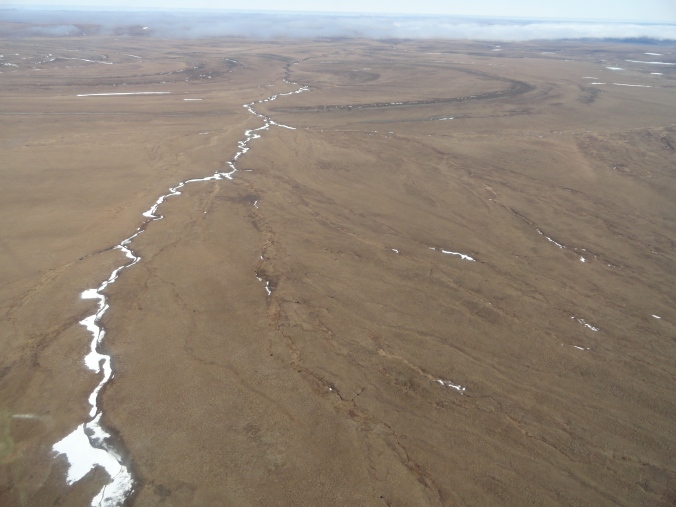

Most of our days are filled with riding snow machines for long hours, searching for tracks and sign of new wolverines in the foothills of the Brooks Range, or in the many river floodplains that transect the tundra. During these times, with earplugs in, our heads enveloped in full-face helmets, and wrapped up like the Pillsbury Dough Boy in warm bibs and jackets, it’s easy to feel removed from the environment. However, in the couple of hours it took for this young male to be fully recuperated for release, the five of us were treated to more than the gift of this new wolverine. It started with just a few wisps of aurora across a night sky lit only be a thumbnail of a moon and stars. But the aurora grew in intensity to a truly breathtaking display over our temporary wolverine camp – a swirling morass of color that covered the sky at its zenith. At times, the surging colors looked to be within arm’s reach, dancing just above our heads. It was as if the light show over the tundra was just for us and this wolverine. Once released, he loped away in that characteristic 3×4 gait of wolverines, passing out of range of our headlamps, and leaving tracks for us again – but now also breadcrumbs of locations, relayed to us by distant satellites.

Lead WCS wolverine researcher Tom Glass checking the wolverine prior to handling. Photo credit: Tom Glass.

In the next 24 hours, the animal traveled over 20 miles south into the Brooks Range. He scaled 6,500 foot peaks and precipitous ridges, demonstrating a typical wolverine disregard for topography. The data he provides us will not only paint a picture for male home range movements and activities during the breeding season on Alaska’s North Slope, but also possibly how he relates to other animals that we are monitoring in the area.

The northern lights tinged with color on our trail home. Photo credit: Matt Kynoch.