Muskoxen at Cape Krusenstern. Photo T. Haynes

A herd of muskoxen waited on shore as we approached the beautifully rugged and remote coast of Cape Krusenstern in the Western Arctic by boat for the first time. Having never seen muskoxen in the wild, our crew was elated. However, we weren’t there to study muskoxen- we’ll leave that to Joel Berger, another WCS scientist who’s been studying the animals for years. Rather, we were there to study the diverse fish communities that inhabit the mysterious waters of coastal Arctic lagoons. Luckily, the muskoxen decided to stick around for the season and turned out to be entertaining neighbors.

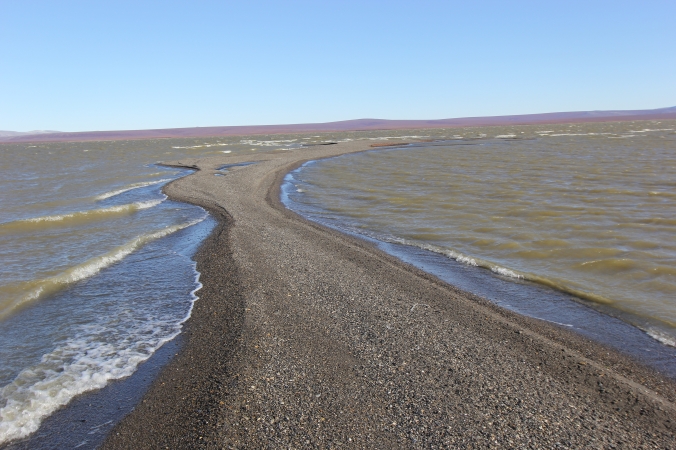

Hauling in a net at one of the lagoons of Kotzebue Sound. Photo R. Sherman

The coastal lagoons of Cape Krusenstern National Monument and Bering Land Bridge National Preserve had far more to offer us beyond muskoxen. Arctic lagoons are among the last naturally functioning lagoons in the world and are habitat to a wide array of animals, including a host of migratory birds such as loons, terns, and waterfowl; and a diversity of fish. The lagoons play a key role in the subsistence fisheries of coastal communities; the local fishermen consider the lagoons as a place where the “fish come to grow”.

Marguerite Tibbles holds a sheefish. Photo T. Haynes

Staring at Google Earth images, reading research papers, and discussions with experienced people can only prepare you so much for a summer on Alaska’s Arctic Coast. Getting there and experiencing it yourself is a whole different story.

The Arctic’s rugged, untouched feel gives you the impression that you’re on some exotic planet, teeming with strange and unusual plants, mammals, birds and fish. For a fish ecologist such as myself, these lagoons represent one of the few aquatic systems in the world that still hold much of their mysteries. There has been a relative lack of research conducted on Arctic lagoons. In other parts of the world where access is easier, scientists can dedicate more research to each waterbody. However, the Alaskan Arctic, particularly here in the shallow waters away from comfortable live-aboard research vessels, remains an isolated frontier, resulting in a relative paucity of scientific research. It’s a place that is simply difficult to get to and challenging to live safely in, never mind collect data. This type of challenge is why being a scientist is so enthralling for me – the prospect of discovery and the challenge of working in a demanding, but fascinating and wild environment.

As a small crew of 3 people tasked with conducting fisheries science in five large lagoons, we were cautiously enthusiastic, as we knew that the summer was going to be incredibly rewarding as well as severely demanding. Our summer involved hopping from camp to camp on small planes, bouncing around in boats, setting and pulling nets, and being up to our elbows in lagoon water and fish. We found that chest waders and five layers of clothing is the vogue fashion for lagoons research, however, dressing for success in the Arctic was only one of our many challenges.

The unforgiving environment of the Arctic has little to offer in terms of amenities and also magnifies all the logistical challenges of fieldwork. Having an engine break down can quickly become a serious situation in a lagoon that is accessible only by float plane, and only in flyable conditions! Simply moving people and gear around via small aircraft is costly and requires careful planning. Weather plays havoc with the best laid plans. On regular occasion, we found ourselves huddled for warmth in creaky cabins shaking in the wind, waiting for days until storms subside, or waiting patiently on a beach wondering if the plane can pick us up. Fog often kept planes grounded in Kotzebue, stranding us for days at a time. However, careful planning in the Arctic includes preparing for all eventualities. We always carried extra supplies, camping equipment and an attitude that each problem we encounter is simply a part of the adventure.

Looking for fish amongst the ice in a late-season net haul. Photo M. Tibbles

We were very pleased with the information that we were able to gather this summer…we met the summer’s challenges well, collecting useful data that builds the understanding of the lagoons. Some notable highlights include:

– Lagoons are used by both marine and freshwater fish, and we are still discovering species that have not been recorded in these lagoons before.

– Mysids, a shrimp-like crustacean, are superabundant and are a major dietary item in the diet for most lagoon fish

– Ninespine stickleback, a diminutive and seemingly unassuming fish, is highly abundant and are important in the diet of larger fish species such as sheefish.

– The fish community composition and fish abundance are strongly driven by the connectivity of the lagoons – fish time movement in and out of the lagoons to take advantage of seasonal access

– We appear to be the first to document pond smelt in these lagoons. Pond smelt were a locally abundant fish species, however, very little is known about them. Pond smelt likely play an important role in the trophic dynamics in some lagoons.

The National Park Service, Wildlife Conservation Society, and Native Village of Kotzebue have recognized the ecological and subsistence importance of Arctic lagoons. By supporting this research, these organizations are creating a stronger understanding of Arctic lagoons, including the fisheries resources that local communities depend on. Having muskox as supervisors of our daily progress is just an added perk of the job!